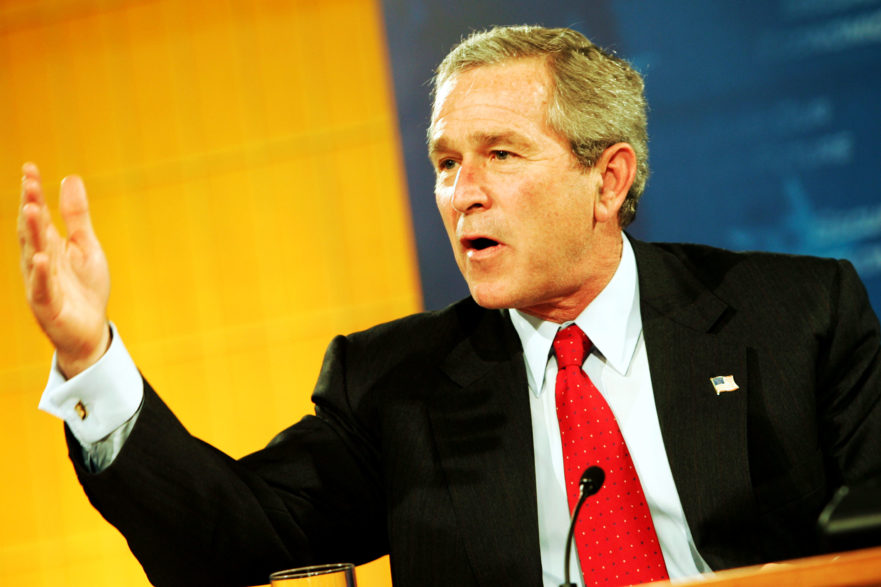

Above: Photo by Jay L. Clendenin-Pool/Getty Images

President George W. Bush gestures while speaking to corporate executives, economists, and academics during a two-day White House Conference on the Economy on December 15, 2004. The White House held the conference to defend the Bush Administration’s economic policies.

By Alex Kane

Former economic aides to President George W. Bush tell TYT that members of his economic teams argued before its passage that a 2004 bill to slash corporate taxes on overseas profits would not boost domestic job creation—casting doubt on Trump Administration claims that cutting taxes on overseas profits will spur U.S. job growth now.

The Bush plan created a one-year tax holiday in which corporations could repatriate overseas profits and pay taxes on them at a rate of just 5.25 percent. Under the Trump tax-policy outline released last month, it remains unclear what proposed rates might be for either a one-time holiday or on future profits.

(See sidebar: What We Know About Cutting Taxes on Overseas Profits to Create Jobs)

In separate interviews, former members of the Bush Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) and National Economic Council (NEC), as well as the former chief of staff for the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, each confirmed to TYT that there was widespread opposition to the tax holiday inside the White House at the time. Some of them said they oppose it now, as well.

“When the tax repatriation holiday was being discussed within the White House, the big issue was whether it would induce businesses to invest more and hire more workers. In various meetings, the CEA argued against this view,” said former CEA Chair Harvey Rosen, who served on the council from 2003 to 2005.

“After my CEA colleague Kristin Forbes returned to MIT, she published academic research which showed that the repatriation holiday had no discernible impact on companies’ investment and hiring decisions,” Rosen said.

Brian Reardon, the principal tax aide for Bush’s National Economic Council, confirmed that the CEA opposed the measure beforehand, but said the NEC—a separate group of economic experts—was more ambivalent.

“The official position of the White House was that we weren’t crazy about the repatriation portion of it,” said Reardon, who said he was personally agnostic on the matter.

Although the CEA provides economic research and policy advice to the president, the group also told Congress about their concerns. On October 4, 2004, Bush Treasury Secretary John Snow revealed key takeaways of the CEA’s analysis in a letter to Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), then chairman of the Finance Committee.

The full analysis has never been made public, but the letter was entered into the congressional record days later. In it, Snow wrote that the Bush Administration “has concerns regarding the fairness of the repatriation provision … U.S. companies that do not have foreign operations and have already paid their full and fair share of tax will not be able to benefit from this provision. Moreover, the Council of Economic Advisers’ analysis indicates that the repatriation provision would not produce any substantial economic benefits.”

Bush ultimately signed the legislation creating the tax holiday, as part of a much larger jobs bill that had bipartisan support, including from some liberal Democrats.

But according to George Yin, the chief of staff for the U.S. Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation from 2003 to 2005, Bush himself was not a fan of the idea, even before he signed it into law.

Yin told TYT what a Treasury Department official relayed to him at the time about Bush’s thoughts on the proposed tax repatriation holiday.

Yin said that in June of 2004, “When President Bush was … told about the provision, he was meeting with some of his top tax experts as well as some political people, and they explained to him what the nature of the proposal was and all of this, and the word I got was that his immediate reaction was, ‘Oh, well, we can’t do that.’”

Yin said, “My impression was that he reacted negatively to the concept of retroactively changing the tax rules in favor of certain taxpayers.”

A wide range of studies published after the 2004 repatriation holiday took effect confirmed the CEA’s predictions that the measure would not help the U.S. economy. Those studies concluded that the tax holiday did not boost investment or domestic employment, and found that many companies cut jobs instead.

The new accounts of internal skepticism about the effectiveness of a tax repatriation holiday come as congressional Republicans are crafting a new package of tax cuts on overseas profits.

“We do envision imposing a one-time low tax rate on all overseas profits which will bring lots of money back home to the U.S.,” Trump NEC Director Gary Cohn told the Financial Times in August.

Rosen, the former Bush CEA chair, told TYT that he believes tax reform is needed—but that another repatriation holiday should not be part of that reform.

“The U.S. system of business taxation requires permanent reform, and such reform should include a move to a territorial system of taxation for income earned abroad,” said Rosen. (A territorial tax system would tax companies only on income earned domestically.)

Rosen said, “A standalone repatriation holiday does not satisfy this criterion, so I do not support it. However, a repatriation holiday that was included as part of [a] transition to a territorial system could be a sensible policy, although, as usual, the details would be important.” The Republican tax-plan outline, released after Rosen spoke with TYT, appears to propose such a transition.

Yin, the ex-chief of staff for the U.S. Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, also said he opposes a tax holiday.

“It just seems like a windfall [for corporations], which, from the standpoint of good policy, it’s hard to think of how that benefits the country,” said Yin.

The current federal corporate tax rate is 35 percent, though in practice the effective corporate tax rate on profits averages about 22 percent because of loopholes and deductions, according to a Treasury Department analysis of the years 2007 to 2011. Trump has said he wants to reduce the corporate tax rate to about 15 percent, although the new outline calls for 20 percent.

The Administration says that reducing the corporate tax rate on overseas cash will boost domestic investment and create jobs.

That was also the rationale for the bill President Bush signed in 2004. Known as the American Jobs Creation Act, it directed companies who repatriated their profits to reinvest that low-taxed money for purposes including “the funding of worker hiring and training, infrastructure, research and development, capital investments, or the financial stabilization of the corporation for the purposes of job retention or creation.” The bill said the low-taxed profits were not to go toward “executive compensation.”

Yin told TYT that Capitol Hill staffers looking at this provision, including himself, were concerned that it was not enforceable.

“No matter what you provide in the statute, in terms of limitations of how the money might be used when it’s brought back at this reduced tax rate, it seemed to us that most of it was just for show—that there was just no way that we would ever be able to enforce those rules,” said Yin. “[It’s] extremely unlikely that anybody who took advantage of this provision would ever get audited by the IRS, and the IRS would be able to establish in court that, in fact, one or more of the conditions hadn’t been complied with. It just seemed extraordinary unlikely, and in fact, to my knowledge, I don’t think has ever occurred, even though there have been some efforts to figure out what happened to the money.”

What happened with the money was apparently not a mystery to Bush. After the repatriation holiday failed to create jobs, he reportedly said he would never repeat that mistake. Bush’s comments were reported on multiple occasions by former President Bill Clinton.

In a 2015 interview with Inc. magazine, Clinton said Bush had told him he’d “never fool with” such a policy again because it was not used to create jobs, despite companies having told Bush the money would go to jobs and pay raises.

President Bush, according to Clinton, “felt personally burned by his constituents.”

Clinton has recounted this story more than once. He elaborated on it just last year in an interview on CNBC.

“I would like to see a repatriation initiative that works a little bit different than when President Bush signed one,” Clinton said. “[Bush] got so mad that he signed the … repatriation bill and he said none of it was reinvested!”

Bush has never publicly denied Clinton’s account. Bush’s office did not return TYT’s request for comment.

Comments

So both Bush admits that multinational corporations are his constituents, apparently Clinton agrees & people can’t see that both parties are owned by the same money, WTF